It is very hard to propose one singular theory on book illustration history that would be linear and easy to follow. Book illustration origins involve several distinct and simultaneous channels of development all around the world and it’s traced from its first notion in cave art to the early 20th century.

Illustrated texts pre-date the printed book by thousands of years but unfortunately much has been lost from early civilizations, such as Greece, China and Rome due to the fragility of the material. Ancient Egypt is the exception because of the durability of papyrus and the fact that the material was carefully and deliberately buried has ensured some remarkable survival (The History of Book Illustration, 2022). Paper arrived in Europe by the 12th century from the Far East, where printing, paper, and illustration had existed as early as the Buddhist Diamond Sutra, dated A.D. 868.

But illustrated books did not begin to proliferate in Europe until 1472, and then only in Germany and Italy, the heart of the Continent. Superior techniques for making engravings, etchings, and woodcuts of illustration were soon invented in Germany and the Netherlands. Illuminated manuscripts, produced slowly one at a time, had long since become too expensive for scholars and less wealthy individuals to buy. Private libraries were small and public libraries did not really exist.

The invention of the various printing techniques in Europe was separate development over five hundred years later compared to the East, but once the idea of illustrated printed books took hold in the West, the price and time advantages were enormous and demand was present. This is due to the growth of universities and increasing literacy. In the late fifteenth century, Florence had more woodcarvers than butchers, suggesting that art, even more than meat, was a necessity of life. This was true not only for the wealthy but also for those of more modest means. In North America, there was no printing until the 17th century. Due to Portuguese voyages, Western printing was brought to India, China and Japan.

Jumping a few centuries ahead, in the 1980s with the help of a generation of new art directors, they made an important contribution to a new form of conceptual illustration- a fresh way of storytelling. It was an inventive, interesting time for illustration, fueling imagination, creativity, and resourcefulness. Fresh faces started breaking into the field, and others looking to spruce up old styles and get some work available, but they lacked understanding of the evolution and personal intent it takes to make a good picture. They simply copied styles. It didn’t take long before the concepts became trite and painfully obvious. Art directors and designers sensed this even as they commissioned it. Pragmatic and busy- with too much work and too little help- they found little in the illustration to excite them. Illustration became an element in the art director’s design, like type and photography.

But luckily the age-old discipline of illustration has enjoyed something of a renaissance in recent years. For a discipline that was in a state of crisis and almost on the verge of extinction for the best part of the 1990s (because of the technological boom), this was a timely resurgence. Nonetheless, it has become a popular discourse for how illustration can be rejuvenated by a reaction to digital dominance, even if that reaction is not an outright dismissal and how can the two co-exist (Hyland and Bell, 2003).

The “Sistine Chapel” of prehistoric art has been found just over a century ago, in 1879, by Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola. The discovery of cave art radically changed the way Stone Age people were perceived.

“The following year de Sautuola published a very modest account of his work in Altamira. In it, he described in detail the artefacts recovered during his excavations. He also identified the exquisitely painted bison and linked these to the carvings of bison he had seen in Paris a year or so earlier. He concluded that the paintings were executed by the same people who were responsible for the stone and bone artefacts being excavated from the caves. Sadly, he was ridiculed for his conclusions and was even accused of making the paintings himself. He died in 1888 a ridiculed and broken man.

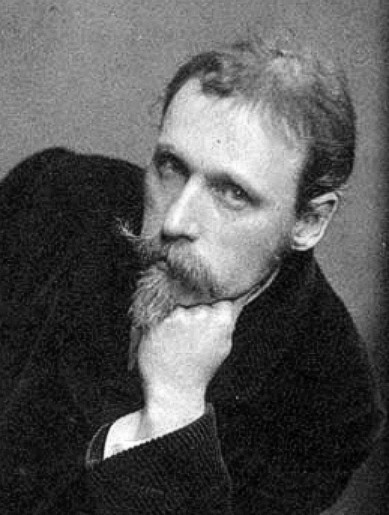

One of the greatest illustrated books of the 15th century, because of the mastery with which the woodcuts were designed and executed by the artist himself, is Albrecht Durer’s Apocalypse of 1498. Printed and published by the artist himself, the many copies that probably once existed may very well have been broken up so that the woodcuts could be framed separately.

He is credited with bringing the Renaissance to Northern Europe

One of the marvellous surprises for anyone who handles astronomical books of the 16th century is to come upon volumes containing movable disks, the so-called volvelles. Not only are moving parts found in a few spectacular monuments of the printing art, but many rather unprepossessing octavo textbooks also include these charming assembles. The small volume by Petrus Apianus displayed an outstanding use of volvelles for teaching purposes.

Walter Crane was an English artist and book illustrator. He is considered to be the most influential, and among the most prolific, children's book creators of his generation and, along with Randolph Caldecott and Kate Greenaway, one of the strongest contributors to the child's nursery motif that the genre of English children's illustrated literature would exhibit in its developmental stages in the later 19th century.

Crane's work featured some of the more colourful and detailed beginnings of the child-in-the-garden motifs that would characterize many nursery rhymes and children's stories for decades to come. He was part of the Arts and Crafts movement and produced an array of paintings, illustrations, children's books, ceramic tiles, wallpapers and other decorative arts. Crane is also remembered for his creation of a number of iconic images associated with the international Socialist movement.

Norman Percevel Rockwell was an American painter and illustrator. His works have a broad popular appeal in the United States for their reflection of American culture. Rockwell is most famous for the cover illustrations of everyday life he created for The Saturday Evening Post magazine over nearly five decades. Rockwell found success early. He painted his first commission of four Christmas cards before his sixteenth birthday. While still in his teens, he was hired as art director of Boys’ Life, the official publication of the Boy Scouts of America, and began a successful freelance career illustrating a variety of young people’s publications. Rockwell was a prolific artist, producing more than 4,000 original works in his lifetime. Most of his surviving works are in public collections.